Classic network topology

Typically, in a classical infrastructure, network architects design multiple networks according to the security wanted for the elements residing in the network. For instance, for a web infrastructure, you could have a front network, where the webservers live, which is accessible from the Internet on ports 80 and 443 ; and a back network, for the database servers, which is only accessible from the front network. This is a fine design, because it allows you to manage security between the networks with firewalls and routing restrictions.

If you have a complex application that deals with sensitive data, you can push it further with what I call an onion architecture (nothing to do with TOR): the networks are layered one on top of the other. The more sensitive the data, the deeper the network it resides in. Placing firewalls between each layer gives you fine-grain control on what has access to what. Even more interesting, if your application implements a good circuit-breaker pattern, your security guys can just flip a switch on the firewalls to protect all or part of the data.

Network security on AWS

In AWS VPC, there are two main security features: Network Access Control Lists (NACLs) and Security Groups (SGs). They are quite different and both serve a different purpose.

Network Access Control Lists

NACLs are the closest to what a firewall is in a classic infrastructure. They are associated with a subnet and allow you to restrict the flows between subnets. Here are the properties of NACLs:

- They allow all inbound and outbound traffic by default,

- They are composed of an ordered list of rules,

- Like IPTables, first matching rule wins.

However, the NACLs have a few restrictions:

- 20 rules per NACL as a soft limit, 40 as hard limit but with a potential performance impact.

- NACLs are stateless! This means that they don’t follow TCP or UDP connections and that if your machine makes an outbound connection to port 80, you have to explicitly allow the response on a port that will be, most of the time, random.

Statelessness was a huge pain in classic firewalls, and it still is on AWS. This is why I recommend not to use NACLs if it can be avoided or only to blacklist a few sensitive ports.

Security groups

Security groups are the main network security feature in AWS. When new on AWS, people tend to treat them as firewalls, which they kind of are, but they are much more.

A security group is an object associated with an EC2 instance (or an ELB, or a RDS instance, etc.)1 that gives you control on which network flows are allowed for this EC2 instance. Here are the properties of Security Groups:

- They block all traffic by default,

- The only possible action is ALLOW,

- You can reference other security groups in a rule,

- You can attach up to 5 SGs per interface (soft limit),

- Each SG can have up to 50 inbound and 50 outbound rules (soft limit),

- They are statefull.

These properties seem quite normal at first glance but two of them really make all the difference: multiple security groups per instance and references to other security groups.

What does it mean? As their name indicates, security groups are used for grouping, on a security level, instances. Another way to name security groups could have been “security roles”. Once you have internalized this notion, security groups become very different from firewalls: when manipulating rules, you don’t see it as “allowing this subnet to connect to this instance on this port” anymore, but as “allowing this group of instances to connect to this other group of instances on this port”.

Imagine you have three types of EC2 instances, everything in the same network:

- database servers,

- servers for application A,

- servers for application B.

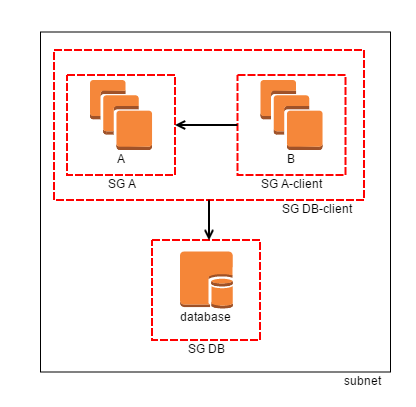

Both A and B must be able to access the databases, and B must be able to make requests to A. You can then create 4 security groups: DB-client, A, A-client and DB. Associate A to A, A-client to B (because B is a client of A), DB to databases and DB-client to both A and B (because both are database clients). You can then apply the following rules:

- Allow

DB-clientto make database connections toDB, - Allow

A-clientto make requests toA.

With this simple set up you have a fully working and completely secure topology, without having to manage rules at the network level with NACLs or anything else.

AWS networking architecture

In a classical network architecture, one could also manage filtering machine by machine, with IPTables rules on each machine, but almost nobody does that because it’s very complicated to manage and not that easy to set up (not talking about the risk of locking yourself out of the servers). Security groups give you an easy way to manage security at the instance level. The consequence is that you don’t really need to set up filtering on the network border anymore.

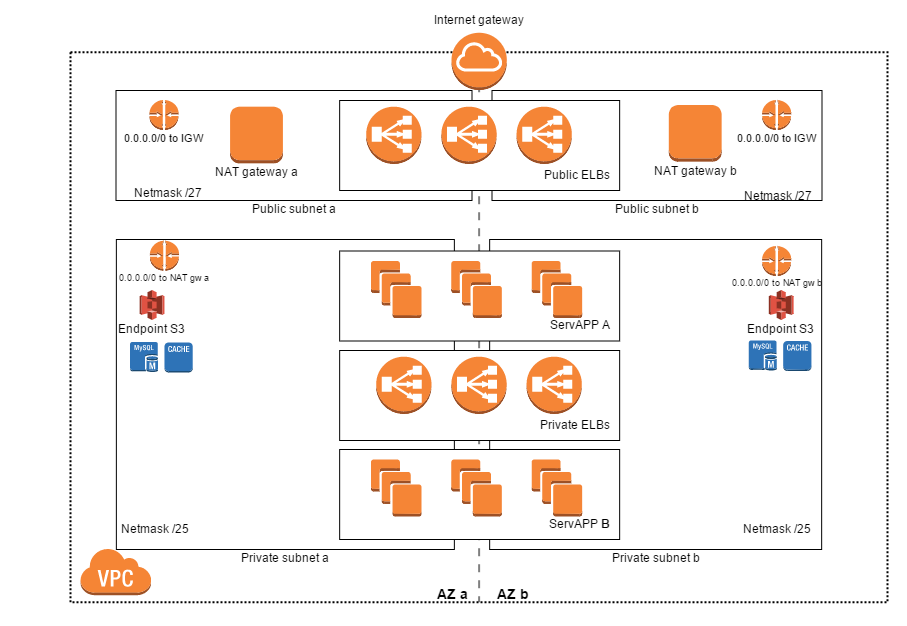

And if you don’t need firewalls between networks, you can merge almost all networks. In the end, you only need 2 or 3 categories of networks:

- Public networks, where instances can have a public IP. But in practice, your instances should never have a public IP: all traffic should go through an ELB. This means that in the public networks, you only place ELBs and NAT gateways. Those networks usually do not need to be very big.

- Private networks, where all your instances (and possibly some private ELBs) can live. All instances have access to the Internet through the NAT gateways in the public networks.

- Private networks with special routing: some of your instances may need to access services through a VPN or a DirectConnect connection. If you want to restrict the access to those services to the EC2 instances that need them, you can create private networks that have an AWS route table configured for accessing those services (whereas the “normal” private networks don’t).

Some other important points:

- All subnets have a route to the whole VPC and you cannot delete this route. You cannot manage security through routing for internal VPC traffic.

- Managing routing at the instance level is very hard and possibly dangerous if the gateways IPs change for a reason or another. Don’t bother and always manage routing with AWS route tables.

- EC2 instances can have more than one network interface, possibly in different subnets. With the two previous points in mind, I never saw the need for more than one network interface.

Here is a diagram of what the network topology I am describing looks like:

Conclusion

I hope that this post helped you in shifting your mindset about networking on AWS. To sum up: create as few networks as possible, manage security through roles (i.e security groups) and routing through AWS route tables. I had in mind to create a CloudFormation template for setting up this topology but AWS beat me to it. You can find the template here and the instructions here.

If you follow those rules, you will find that managing networks on AWS is actually quite easy and after a while you will find that networks tend to disappear from the list of things you worry about: you know they are here, but you don’t think about them very often. On the other hand, if you try to replicate a classic network architecture on AWS, you will quickly find that it is very hard and not adapted at all.

Happy networking!

1: Technically, security groups are associated to ENIs (elastic network interfaces), but as seen in the last section, you almost never need more than one ENI per EC2 instance.